Twice I went to Jamshed Memorial Hall. First to see the works installed in this interesting building on M.A. Jinnah Road, an old and busy road leading past the city centre to the docks and littered with shops and offices built a long time ago. Then the next day again to witness two performances that took place there. The building was named ‘Jamshed’ for an ambitious past mayor of Karachi, has a Montessori school on its upper floors and has or had some connection with Karachi’s Theosophical Society. For the biennale artist Tazeen Qayyum had created a ‘site-responsive’ work Façade decorating the building’s front with cut-out paper insects, looking very much like cockroaches, but also as a beautiful lot together.

‘Yes, it is intended to look like a mushroom,’ is what the attendant told me. A mushroom three times the size of a human being and grown by the artist assembling together a whole range of material objects that were wrapped in plastic and no longer recognizable or relevant as anything else than building material for the mushroom Where lies my soul? Except perhaps for the head of a horse seemingly busy to escape at the top, no doubt a horse lost in many an ancient belief or mythology. At the bottom of Munawar Ali Syed’s mushroom there were red lamps adding a glow to the large installation which was placed at the very centre of the Jamshed Memorial Hall’s theatre space.

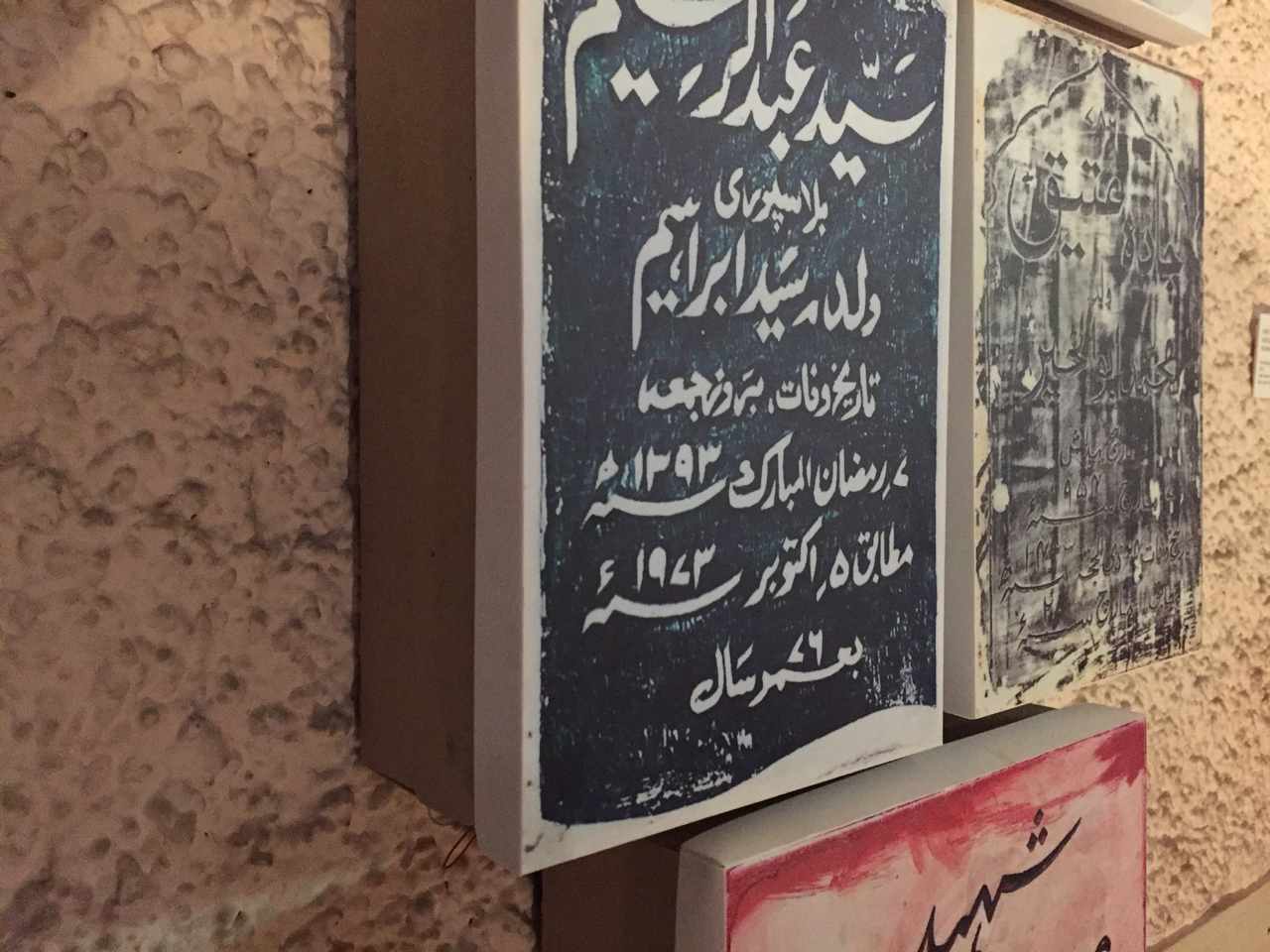

I kind of enjoyed it and the soul isolating itself from the material world seemed to work – intentionally or not – together with several installations of simpel lightboxes on the walls of the hall. Although only made of cardboard, the size of boxes a pair of gymshoes may be sold in, with LED lamps and a timer to switch the lamps on and off it functioned very well. On transparant paper lids these boxes had photo’s of a diverse collection of gravestones, which this visitor presumed the artists had photographed in Karachi, bearing witness to the different sorts of people that dwell in this city. The word ‘katbay’ in the title did not explain itself, perhaps it is a local cemetery.

I would have missed it, if not the artist had pulled me by the sleeve and told me that she was starting a performance in the hallway of the first floor. Repertoire was its title and it happened in the middle of a busy school, with female students turning their heads in surprise to look through the door of their classroom and schoolboys passing the stairs being fetched by their fathers. Artist Waheeda Baloch sat at a teacher’s table and had assembled on the floor around her four students of her own. All were busy with their books, each having a different subject ranging from geography to perhaps literature and each was holding two or more pens, one of which seemed to be with green ink. They were not really studying the books, but crossing or drawing in them with alternating the green and other pens. Crossing out and adapting the content of the book. In the case of Waheeda herself she had a book with pictures of a temple and was using some kind of Tipp-Ex correction fluid pen to erase the images of statues on that temple.

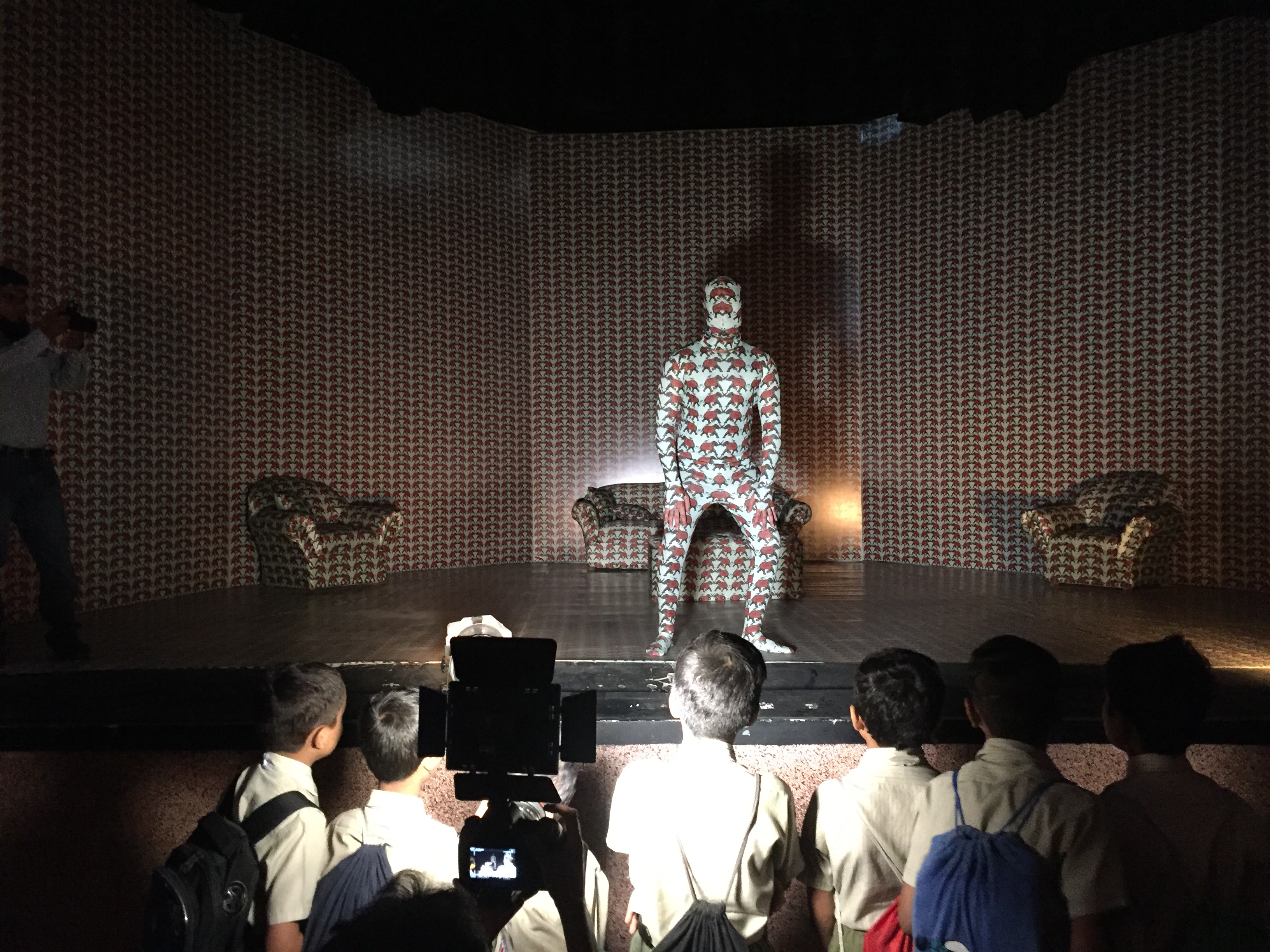

Downstairs again there was another performance. This time on stage. Of and on that stage the walls and all the furniture was wrapped in wallpaper or cloth featuring two elephants fighting, their trunks entangled. It is about ‘peace and tranquillity’ is how, when I asked him what these elephanst meant to him, an official of the venue landed for me his interpretation. The artist too was on the stage wrapped entirely in the same cloth as everything else and simply moved about a bit as perhaps an elephant standing at ease in a comfortable swamp might do. Indeed, it was peaceful. Elephant in the room was the performance’s title and the artist was Muhammad Ali, also known as Mirchi. Before rising to perform on two legs the artist-beast had spent some time on the wrapped couch waiting for two vans with guests to arrive a bit late, but the charming result of that delay was that his performance happened exactly as young pupils, both boys and girls were leaving class – there is a Montessori school on the higher floors of the building. With curiosity the children joined the front ranks of spectators.

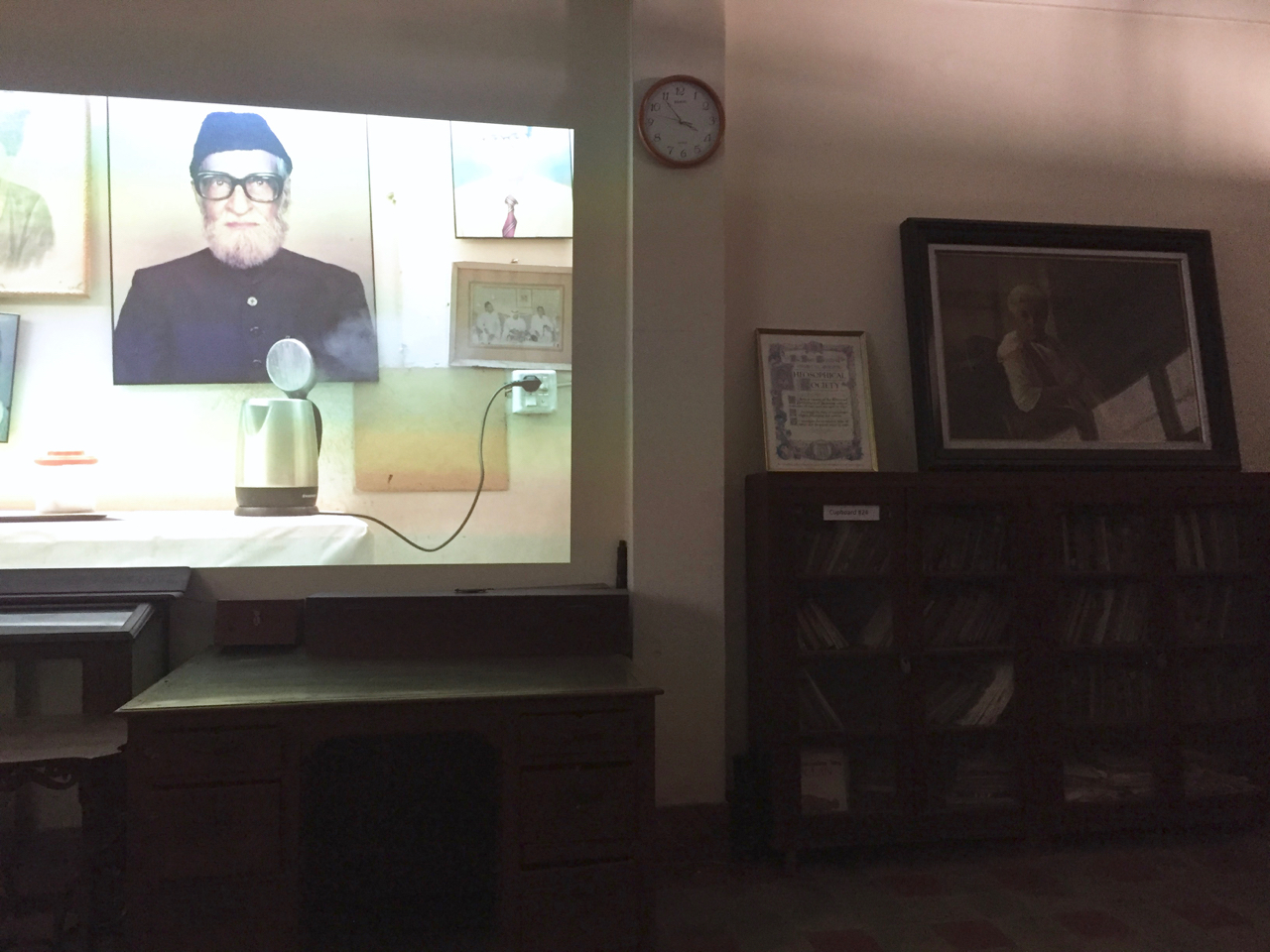

On another floor of the building in a space which looked like the library or boardroom of the former Theosophical Society a multi channel video installation was presented with small screens behind glass doors between books that looked no longer relevant to the community of readers and a large screening on a wall. Some antique chairs that came with the location were arranged for the audience to sit as in a cinema.

Madiha Aijaz was the artist of These silences are all the words. The main video lasted 5 minutes and was made in one of the city’s public libraries. Taking the inside of these libraries as a starting point to meet intellectuals the artist aims to explore through the recorded conversations or fragments of what is said the city outside. In a short explanatory note it also says: ‘to see how the ideas of conformity and futility are playing out in these spaces.’ It falls short then of mobilizing people or should it be interpreted as a call for more intellectual rigor in Karachi? What stuck in my mind was a line that suggested that people were losing their ability to speak in Urdu and in English, losing competency in both languages.

On my first visit I climbed all the stairs and ended up on the rooftop where there was no party, but graffiti to admire and lots of sunshine. Mind Palace is how artist Sanki King introduced the cheerful environment he had created and was still kept busy expanding. Some chairs prevented us to walk on a work in progress, was it unfinished or intentionally so to illustrate the mind that never ends its thinking. I am sure it was. I took the opportunity to admire the view towards some neighboring properties.