The title and theme were intended to connect Islam’s holy cities Mecca and Medina with Salt Lake City in the United States, which hosts the headquarters of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or Mormon Church. Mormons, not unlike some Muslims worried about contemporary culture, wish to return to the original practice of their religion, so the idea of this confrontation of the arts must have been that they would politely find each other. Cities of Conviction is the most charming book so far that has followed from a ‘struggling for some freedom’ exhibition in London in 2008, branded ‘Edge of Arabia’ by its British and Saudi Arabian initiators. In Utah in 2017 the organisation had transformed into something named Cultrunners and was helped and financed by the public relations budget of the Saudi Arabian state oil company Aramco, dressing itself as the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture and branded ‘Ithra’ – who knows what that means? It’s a bit like a Russian doll this exhibition structure and married for the event in Salt Lake City with the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, a more easily to understand institution. The exhibition was just one of several by a group of artists from Saudi Arabia touring as a caravan the United States with the stated purpose “to generate people-to-people dialogue and better understanding between the two nations.” In plainer language, it was a public relations effort for Saudi Arabia and, this is the paradox, at the same time valuable support for the artists for who a bit of applause in the U.S.A. may bolster space for free expression in Saudi Arabia. At least, that is what one hopes for and has actually been happening. Strange only was that the tour was initially timed to coincide with the presidential election campaigns, perhaps not favouring Trump at all, but one might not expect Saudi Arabians to embark on such an intervention in foreign elections.

Publication design – Brian Maya

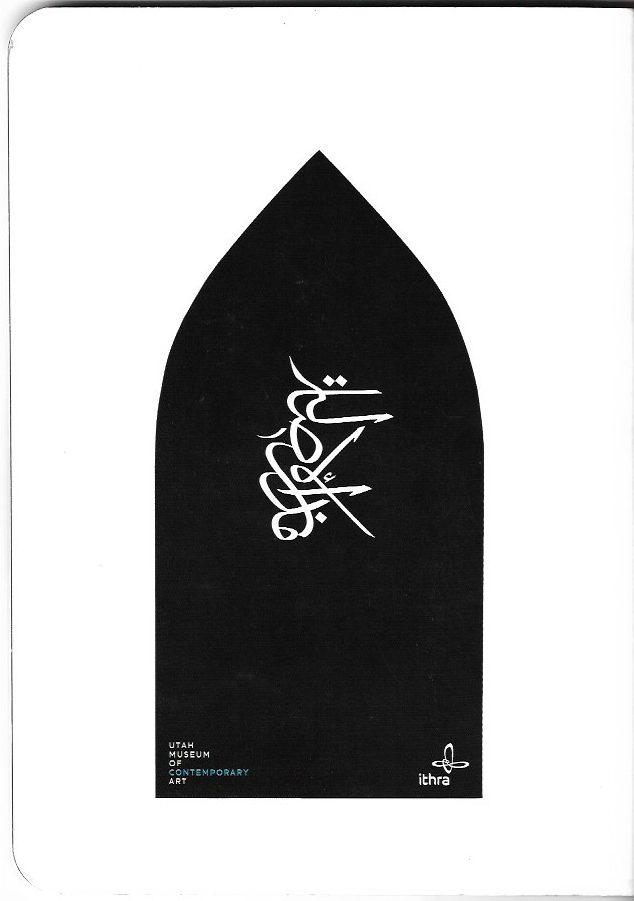

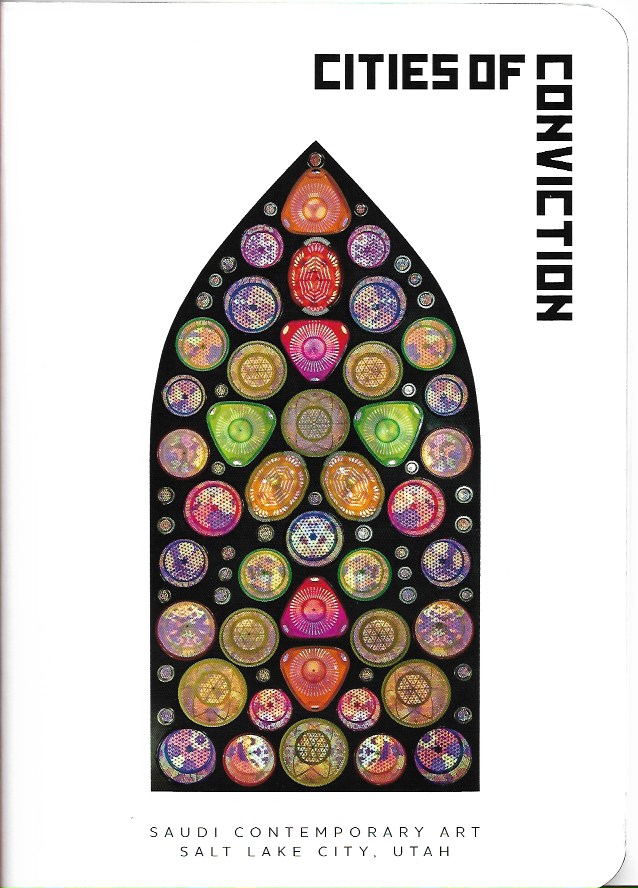

The Cities of Conviction book aknowledges graphic designer Brian Maya, who says about himself on linkedin that he “oversees all in-house design and production operations” at the Utah Museum. I kind of like most things about the book, its slightly taller than A5 format, its not too non-glossy non-glossyness, its white and black combinations and best of all its cover with Rashed Al Shashai Heaven’s Door (2014) which artwork I had seen earlier in Jeddah at the top of public stairs in an apartment block in central Jeddah with one of the collectors turned gallerists, who supported the exhibition in Utah. On the back of the cover calligraphy by Moath Alofi – presumably the title in Arabic – completes the design.

UMOCA – A fearless voice

The Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) introduces itself as having existed since 1931 and being “a fearless voice for innovation, experimentation and dialogue surrounding the topics of our time.” Was there danger in this exhibition and for whom, I wonder, if they speak about fear?

The curator – Jared Steffensen

In his curatorial statement Steffensen connects both the cities Mecca and Medina to Salt Lake City on several points that Saudi Arabia and Utah share. He chooses to see both regions anchored to a specific religion and points out that Mormons have a twice-annual pilgrimage of the faithful to the General Conference at Temple Square, the spiritual center of the Mormon faith. Both countries Steffensen sees as having arisen from the desert and to enjoy a natural resources driven economy – let him perhaps not stress this point in the Hejaz or Asir provinces of Saudi Arabia, where the landscape is different and the revenue from the oil trickles down at a different pace and volume. Pleasing to the ears of some will be that both Utah and Saudi Arabia are said to have “a youth culture pushing the bounderes of their society through relentless individual expression, while maintaining a sense of community.” Surely maintaining a sense of community is on the curatorial wishlist, but what about ISIS, tribalism and rollercoaster nationalism?

Another thing Steffenson does not inform us about, is whether he travelled to or researched Saudi Arabia himself or simply received Cultrunners in curious gratitude, never wondering which laws or permissions of Saudi Arabian authorities allowed the artists to present their work in Salt Lake City. It is my experience with both Saudi Arabian students and the Aramco company in The Netherlands, that they all need specific permission from authorities in Riyadh to go around showing art. Apparently such issues did not present themselves to or bother the curator or director Kristian Anderson of the museum, who remains silent in the publication.

The artists and artwork descriptions

The book has 74 pages containing 37 images and 19 artist biographies and slightly longer descriptions of the artworks than some exhibition books. About Rashed Al Shashai’s Heaven’ Door on the cover of the publication and pictured in this report it reads on page 61 that “these arched stained glass windows are in fact made from kitchenware – plastic colanders and baskets.” The artist sees and illustrates the veneration of God as something to take place in everyday life and not through extravagant public acts that lack sincerity or substance.” Clean you heart and vegetables perhaps before you visit ambitious temples or exhibitions. I enjoy this work and may one day acquire something similar for Greenbox Museum’s collection, which already includes two other, rougher works by the artist acquired in Jeddah in 2013 at a breathtakingly permissive exhibition at Hafez Gallery, where authorities in Riyadh allowed the artist to discuss the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in 1979, ISIS, the Sunni-Shiite animosity and the relevance of a religious learning overdose in the contemporary world.

Road to Makkah

“…perhaps included by Gharem as a subtle critique of the practice of exclusivity”

On page 22 and 23 an old friend of mine, in the collection of Greenbox Museum since 2008: Abdulnasser Gharem’s Al Siraat (The Path) performance video – here mistakenly dated to 2012 – which receives from Steffensen the purely individual interpretation, the safest one, ignoring religious and political connotations that the work definitely had. But then, a little more in line with the ‘fearless’ character which the Utah Museum claims for itself, de text on page 22 also describes Road to Makkah in which work the artist has used stamps to reproduce the road sign forbidding non-Muslims entering the city of Mecca, while embedding with the letters of these stamps a variety of small quotes about the city, which, proposes the book, were “perhaps included by Gharem as a subtle critique of the practice of exclusivity.”

So wow! Somebody actually read the quotes and says it, Gharem puts the exclusivity of entering Mecca for Muslims up for discussion. Both the British Museum and the Dutch Rijksmuseum Volkenkunde didn’t pay any attention to the possibility given here by the artist for some discussion about the issue of forbidding cities for even the most genuine students of their religion. Both European museums exhibited a version of Road to Makkah made in 2011. The version shown in Utah was from 2014 and with slightly different texts, but the overall intention was no different.