De presentatie van een boekje van wetenschapper Martijn de Koning en de status van de universiteit als de oudste van Nederland in zijn vroegere Bourgondische gedaante, waren redenen om de stad Leuven een dagje te bezoeken. Ik trof het, een dunne decemberzon scheen, de grote leeszaal van de bibliotheek was te bezoeken en een verdieping daarboven zelfs een ouderwets leuke tentoonstelling over de romeinse schrijver Ovidius. In de leeszaal trof ik toevallig voor het grijpen een catalogus van de collectie van het Wawel kasteel in Krakau, in welk kasteel de Ottomaanse tenten worden bewaard, die ooit bij Wenen op het slagveld achterbleven. De binnenkanten van die tenten, bewonderen wij nog steeds, als je de foto’s en teksten in dat werk mag geloven1Ik vergat de titel en schrijver van de catalogus te noteren, maar hier wel een link naar de website van kasteel Wawel: ‘About the Museum.’.

Op de tentoonstelling over Ovidius, zonder opsmuk en logo’s van fondsen en sponsers, maar met veel boeken en manuscripten vergezeld van prachtgravures van de Haarlemmer Goltzius, leidde een deskundige gids me rond en herinnerde eraan dat de humanisten in de vroege renaissance ernaar streefden de oudheid ‘ad fundum’ te begrijpen; in zijn basis dus en tot op het bot. Ik tuurde onderwijl in een handschrift van een student die in de dertiende eeuw in Parijs teksten van de Metamorfosen heeft verzameld en dacht aan een salafistische jongeling die me een avond eerder, chattend vanuit Medina, had laten weten een Arabische biografie van de eerste Saoedische koning Abdoel Aziz te willen vertalen in het Nederlands en mij vroeg of de doorsnee NRC lezer daar belangstelling voor zou hebben? Ik wel, maar misschien niet in drie delen.

‘Islamofobie’

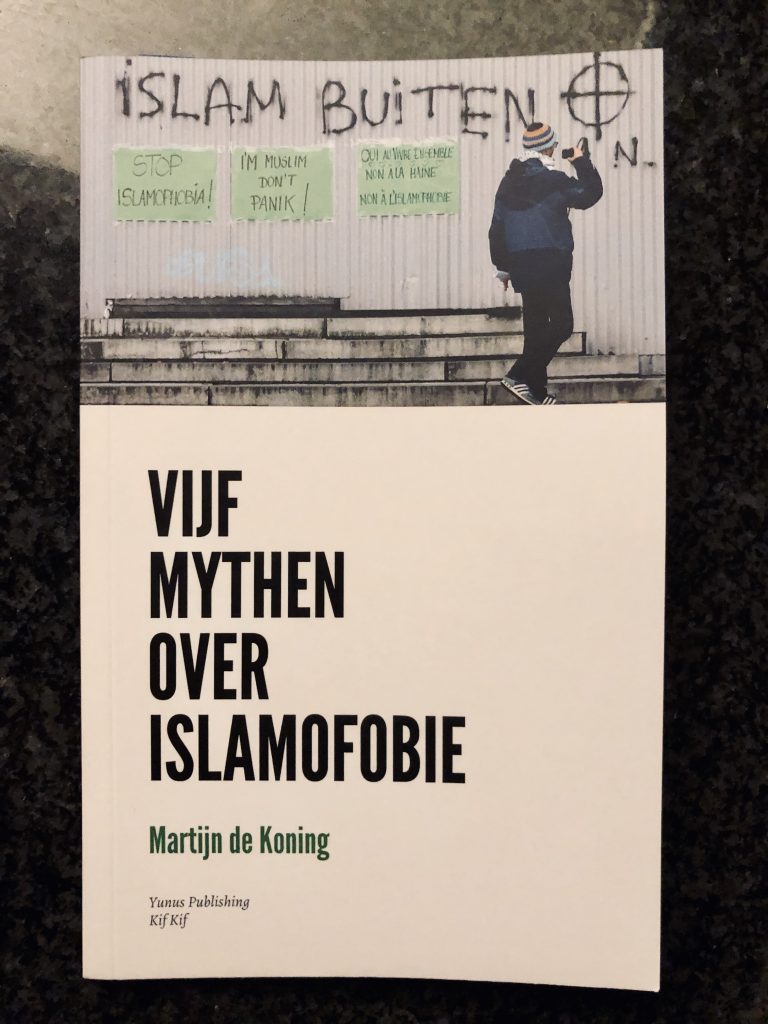

Ik heb aarzelingen in het algemeen bij het bakken van woorden. De één kneedt en verwarmt ‘haatbaard’, de ander ‘islamofobie’. Het is net een wapenwedloop. En of die loop te winnen is, ik weet het niet. Hij is misschien an sich een kwaad. Wat deed activistisch gebruik van het begrip ‘anti-semitisme’ ooit tegen werkelijke jodenvervolging? Wat gebeurt er als bladen zoals Trouw en Volkskrant voortdurend schrijven over ‘moslimmeisjes,’ ‘moslimstudenten’ of ‘allochtonenkinderen’2‘CDA-bureau is bang voor tweedeling,’ de Volkskrant, 20 december 2002, online geraadpleegd op 5 december 2019 maar nimmer woorden gebruiken als ‘roomskinderen’ of ‘luthersgrieten’. Martijn de Koning, een geleerde, heeft kennelijk minder aarzelingen, althans over het woord ‘islamofobie,’ anders publiceerde hij niet met de interculturele beweging Kif Kif3Zie hier hun website: Kif Kif. en financieel gesteund door de Vlaamse overheid Vijf Mythen over Islamofobie4Martijn de Koning, Vijf Mythen over Islamofobie (Antwerpen 2019).. Alle vijf de mythen namelijk werden gebruikt om het woord ‘islamofobie’ zijn bestaansrecht te ontnemen. De Koning poogt dus, uit ergernis (dat zei hij bij de presentatie van het boek in Leuven op 2 december) en vast uit wetenschappelijke noodzaak het begrip steviger overeind te zetten door valse mythen door te prikken.

Dat doet hij goed. Ik zal de essentie maar even benoemen:

– islamofobie gaat de religiekritiek voorbij en is gewoon een vorm van racisme

– islamofobie is reëel en veroorzaakt aanslagen en andere dodelijke vergissingen

Waar De Koning minder in slaagt is het ontkrachten van de mythe dat de term islamofobie werd bedacht om kritiek af te weren door heersers die de islam voor het overeind houden van hun eigen gezag claimen. Zijn boekje is niet zo heel dik, in totaal 72 bladzijden op A5 formaat, maar stimuleerde mij tot een kort eigen onderzoek, waarvan hier het resultaat.

In 1877 al sprake van ‘islamophobes’

Het is de eerste mythe in De Koning’s boekje volgens welke het begrip ‘islamofobie’ een uitvinding geweest zou zijn van de Iraanse geestelijk leider ayatollah Khomeini of van de (Saoedisch gestuurde, volgens mij) Organisatie voor Islamitische Samenwerking in een poging kritiek op hun religie af te weren. De Koning toont echter dat het begrip in ieder geval al in 1910 door een Franse wetenschapper werd gebruikt en dat Khomeini toen net wel was geboren, maar wat jong was voor het bedenken van zulk soort woorden en die internationale organisatie in zijn huidige vorm in het geheel nog niet bestond. Hij heeft dus in beginsel gelijk, zij hebben het woord niet als eersten bijeen gescrabbeld. Het woord is echter ouder dan 1910 en werd na lange tijd in onbruik te zijn geraakt wel degelijk door Oosterse heersers in ‘activistische’ ere hersteld.

Online trof ik dat ouder voorkomen van het begrip in The Athenaeum van 13 januari 18775‘Semitic literature in 1876,’ in The Athenaeum, No. 2568, 13 januari 1877, pp 49-50, geraadpleegd op Google Books op 4 december 2019.. In dit Britse culturele en literaire tijdschrift deed de redactie verslag van alle in 1876 gepubliceerde semitische literatuur en behandelde daarin na het Hebreeuws, het Arabisch. Positief schreef de redactie ondermeer over een pamflet over Arabische figuratieve beeldende kunst en over twee vertalingen in het Frans van ethische en devotionele werken van ene Zamakhschari, een 12e eeuwse islamitische geleerde6‘Al-Zamakhshari,’ lemma op de Engelse Wikipedia, geraadpleegd op 8 december 2019.. En dan volgt een haast vanzelfsprekende verwijzing naar het bestaan van ‘islamofoben.’ Ik geef de gebuikte zin hier maar in het Engels weer: “From these two books some Islamophobes may, perhaps, acquire a little idea of the moral sense of the professors of this religion.” Kennelijk zijn islamofoben lieden die niet verwachten dat islamitische geleerden iets schoons kunnen voortbrengen. Het pamflet over de beeldende kunst moest intussen die mensen de ogen openen die menen dat de islam immer tot iconoclasme leidt. Ik kom zulke lieden bijna wekelijks in Amsterdam tegen. Het in Parijs in 1876 gedrukte pamflet van M.H. Lavoix, Les Peintres Arabes in een reeks ‘Les Arts Musulmans voor de uitgeverij van de L’École Nationale des Beaux-Arts is zo aardig voor een Saoedisch museumpje als het onze dat ik er hier een link naar geef op een particuliere website: Les Peintres Arabes.

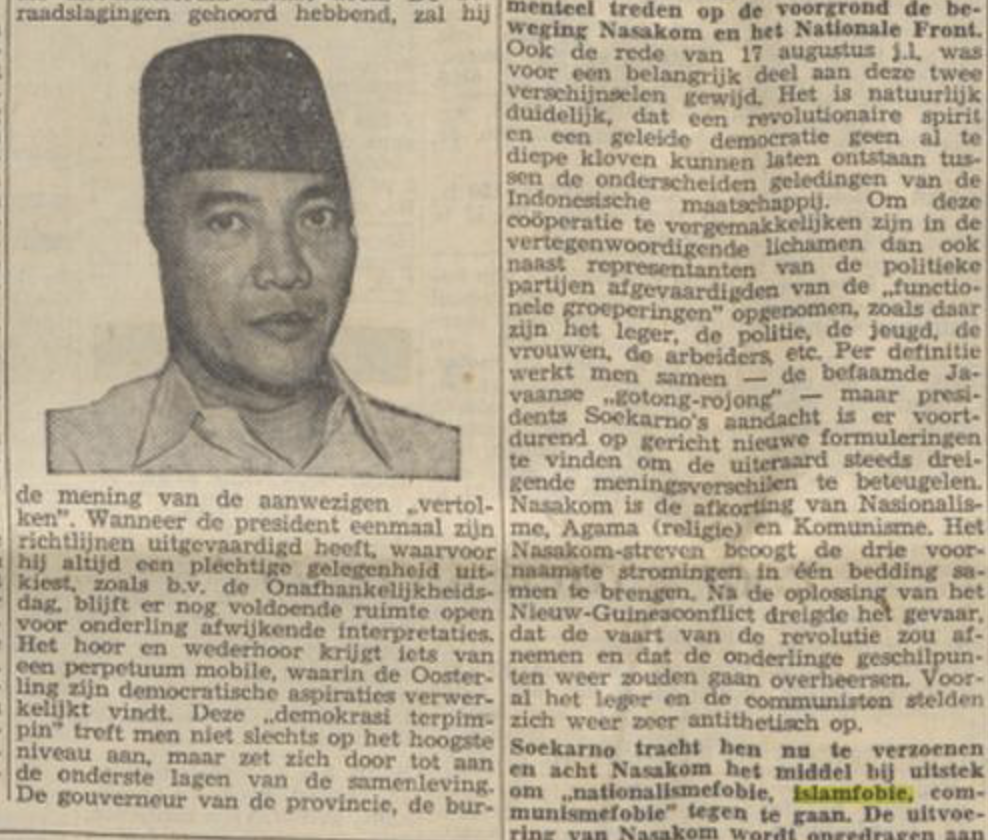

‘Islamfobie,’ Soekarno vond het woord voor Nederland uit in 1963

Deze is wel aardig. Niemand minder dan een voormalig Nederlands onderdaan en eerste president van Indonesië zorgde dat het woord voor het eerst in een Nederlandse krant terecht kwam. Ik zocht in het gedigitaliseerde krantenarchief op de website van Delpher naar een meer specifiek Nederlandse geschiedenis van het begrip ‘islamofobie’ in het publieke, niet academische, domein en vond als eerste voorkomen het woord, geschreven als ‘islamfobie’, in een artikel uit 1963 over Soekarno in een Limburgs dagblad. De schrijver, de Nijmeegse historicus en latere europarlementariër voor het CDA Jean Penders, had als lid van een Nederlandse studentendelegatie de president ten paleize in Djakarta bezocht en Soekarno moet het woord in een toespraak in het Nederlands of het Engels hebben gebruikt. Penders zet het woord als een quote van de president, maar de context is anders dan die welke De Koning zoekt. Soekarno gebruikte het begrip niet om vijandig gedrag van Europeanen te benoemen, maar om seculiere communistische, nationalistische en islamitische Indonesiërs in een nieuwe volksbeweging tot elkaar te brengen7‘Soekarno gaf Indonesië revolutionaire inspiratie,’ door J.J.M. Penders in Limburghs dagblad, 4 september 1963, geraadpleegd op delpher.nl op 4 december 2019.. Het zijn dus niet slechts blanke Europeanen die een onbezonnen afkeer van de islam kunnen hebben, maar ook seculiere Indonesiërs. Behalve islamofobie moesten Indonesiërs overigens ook hun communismefobie en nationalismefobie overwinnen, volgens de president.

Een Russische geleerde wijdt de inval in Afghanistan aan ‘islamofobie’

Het is in het dagblad Trouw dat het woord na 1963 voor het eerst weer in een Nederlandse krant een plaats krijgt8‘Gorbatsjow is zijns ondanks moslimleider,’ in Trouw van 7 september 1990, geraadpleegd op delpher op 8 december 2019. In 1990, na de val van het ijzeren gordijn, wijdt een lid van de Sowjet-Academie van Wetenschappen de inval in Afghanistan aan onwetendheid en meent hij dat in het onderwijs en de politiek meer rekening moet worden gehouden met de eigen ‘islamofobie’ van de Russen. “Niet alleen kennen we de basisfeiten over de moslims niet, maar ook is alle informatie over de geschiedenis, traditie en cultuur van de islam tientallen jaren door onze ideologische dogma’s verdraaid.” Met de juiste kennis, zou Afghanistan nooit zijn binnengevallen, aldus Stanislaw Prozorow die hoofd was van de islamitische studiegroep van de academie. Trouw vindt dat kennelijk nieuwswaardig en vier jaar later ook het volgende.

Dan lanceert Jordanië het begrip in 1994 in ruil, lijkt het, voor de bestrijding van anti-semitisme

Wie ‘islamophobia’ online in meer recente (Engelse) berichten zoekt, vindt een toespraak van koning Abdullah van Jordanië tot het Europees parlement, na een herdenking van de slachtoffers van de aanslag op Charlie Hebdo, met een oproep aan Europa om islamofobie te bestrijden9Jordan’s King Abdullah urges EU to fight ‘Islamophobia’, op de website van Reuters, 10 maart 2015, geraadpleegd op 8 december 2019. Voor Jordanië was dat geen nieuw politiek streven. Trouw rapporteert over dit activistisch gebruik van de term in 1994 in een verslag van een toespraak van de Jordaanse kroonprins Hassan, een in Nederland geziene gast, tot 300 Joods-Amerikaanse ondernemers die Jordanië bezochten na de opening van de Jordaans-Israëlische grens. De prins vertelt zijn ontbijtgasten dat hij mede-oprichter was van een interparlementaire commissie tegen antisemitisme en vraagt zijn toehoorders gezamenlijk in actie te komen in ‘de strijd tegen de islamofobie’ die in het westen wijd verspreid zou zijn10‘Ontbijt met de kroonprins’, in Trouw van 17 augustus 1994, geraadpleegd 8 december 2019. De islamofobie tenminste. Een week later overigens kwam men in Trouw het begrip ‘islamofobie’ weer tegen in een ingezonden brief van een Zoetermeerse imam als iets waar hij al jarenlang tegen strijdt11‘Imam (3)’, ingezonden brief van Ahmed K. El Helou in Trouw van 24 augustus 1994, geraadpleegd op 8 december 2019. Een brief overigens die kennelijk reageert op kritiek op een interview met hem in Trouw waarin hij al sprak van ‘islam-fobie’ en overigens tegelijk het afhakken van handen van dieven aanbeval voor Nederland onder verwijzing naar de diefstal veilige situatie in Saoedi- Arabië. Het is geen makkelijke opdracht, angst als vrede adverteren en tegelijk de mens zijn angst verwijten12‘Imam El Helou: De islam kan Nederland verrijken,’ in Trouw, 12 augustus 1994, geraadpleegd op 9 december 2019.

Na 11 september 2001 pas vaker

Het gedigitaliseerde krantenarchief van Delpher zelf stopt bij 1995. Wel zijn op de website de externe kranten van Krantenbank Zeeland te raadplegen, waarin het woord islamofobie na de aanslagen van 2001 in de Verenigde Staten negentien maal voorkomt in de periode 2000-2009 en zes-en-twintig keer in 2010-2019. Het jaar dat opvalt is vooral 2006 omdat de Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant en andere regionale kranten in dat jaar een groot onderzoek hebben gedaan naar ‘racisme, vreemdelingenhaat en islamofobie’13‘Het is een vreemdeling zeker’, Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant van 3 juni 2006, geraadpleegd op Krantenbank Zeeland op 8 december 2019. ‘De helft van de Nederlanders heeft een afkeer van moslims,’ bleek toen uit een onderzoek van Motivaction voor de krant. Ik vraag me eigenlijk af hoe je zoiets vaststelt en wat het precies betekent, maar om dat uit te zoeken was dit verslagje niet bedoeld. De term islamofobie doet vervolgens weer opgang in 2015 als de gemeente Amsterdam ‘islamofobie’ aan de hand van incidenten gaat registreren14‘Amsterdam. Registratie van islamofobie,’ in de Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant van 28 augustus 2015, geraadpleegd op 9 december 2019. Ook verkiezingsjaar 2017 valt op. Dan verschijnt het woord ‘islamofobie’ in een compliment aan SGP lijsttrekker Kees van der Staaij die daarop handig in zou spelen15‘SGP biedt stevig houvast’, in Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant, 3 maart 2017, geraadpleegd op 9 december 2019. Ook in 2017 is er een artikel over gedoe in verband met een ‘boerkini,’ naar buiten gebracht door ‘CCIF, een Franse organisatie die islamofobie bestrijdt’16‘Zwemster in boerkini krijgt ‘rekening’ van 490 euro,’ in Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant, 8 augustus 2017, geraadpleegd op Krantenbank Zeeland op 9 december 2019. En last but not least, doet Wierd Duk, een domineestelg uit het Walcherse Domburg, een duit in het zakje. ‘Is er te weinig aandacht voor ‘islamofobie’? vraagt hij zich af in een gebalanceerd stukje waarin zowel woorden als werkelijkheid werden ontleed17Over islamofobie. ‘Komt het door mijn hoofddoek?’ in Provinciaal Zeeuwse Courant, 29 april 2017, geraadpleegd op Krantenbank Zeeland op 9 december 2019.

Saoedisch, ‘Habsburgs’ en Joods verbond tegen religiekritiek

In het aan de macht van de paus ontworstelde republiekje dat sinds 1815 als koninkrijk poseert om de revolutiefobie van edelen en heren uit de weg te gaan, kijkt men hopelijk wat aarzelend aan tegen het overigens welgemeende initiatief van wijlen de Saoedische koning Abdullah om samen met beide voormalige Habsburgse landen Oostenrijk en Spanje in Wenen een instituut voor religieuze verzoening overeind te houden dat tegelijk zich inspant om religiekritiek in de zin van belediging van ‘heilige’ heren of zaken tegen te gaan. Abdullah meende het allemaal overigens oprecht, hoewel de instelling ook gewoon een publiciteitscircus was na de aanslagen van 9/11. Ik zag echter ooit een video waarin hij zich zo opwond over ‘atheïsten’ dat het moet zijn dat hij dit woord anders verstond dan Nederlanders dat doen, meer in de betekenis misschien van het woord ‘goddelozen’. Of ‘wetsverachters’. Het King Abdullah International Centre for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue (KAICCIID) liet dit jaar nog islamitische en joodse leiders de handen ineenslaan voor het doen van een oproep om Europa vrij te maken van ‘Islamophobia en Antisemtism’ door ‘hate speech’ tegen te gaan18Muslim, Jewish leaders ask European Institutions to Protect religious expression and counter hate speech’, op de website van KAICIID, 18 september 2019, geraadpleegd op 9 december 2019.

De Koning (Martijn, de geleerde, niet Abdullah) moge dan gelijk hebben dat het een mythe is dat Khomeiny of de Organisatie voor Islamitische Samenwerking de term ‘islamofobie’ heeft uitgevonden, althans daar blijkt in Nederlandse publicaties in het geheel niets van, maar dat buitenlandse despoten, die thuis wat huiswerk te doen hebben, het begrip in Europa pushen, mag best worden waargenomen en vastgesteld, zonder aan de bestaande werkelijkheid van islamofobie voorbij te gaan.

Amsterdam, 9 december 2019

A.H.